Sponsorship history part 1

Sponsorship History Part 1

Although sponsorship has really taken flight over the past few decades as an important marketing communication tool, it has been in existence for much longer than you would think. We retraced the origin and history of sponsorship, and it might surprise you. In this first post, we will focus on sponsorship before the 19th century.

Of course, it had very little to do with the tool that we know today. First, sponsorship was born as a form of patronage or philanthropy used by members of royal or wealthy families. The decision to financially support someone or a project was dictated by the patron’s personal interests, not by company objectives, and exposure was limited mainly to word of mouth.1

330 BCE: The Birth of Sponsorship?

The first “sponsorships” date back to the 5th century BC in Ancient Greece. Initially, sponsorship took the form of a tax paid by rich citizens to finance major competitions and public festivities. These taxes largely contributed to fostering the economic and cultural development of cities such as Athens and Olympia. Paying this tax was a great honour, and some citizens would even voluntarily do so. Those taxed were held in high esteem, and even had their names engraved on marble slabs.

Leonidas was the earliest donor to Olympia whom archeologists have identified. Around 330 BC, he financed the construction of a luxurious building meant to host official guests and prestigious visitors. The building was named after its sponsor, the “Leonidaion,” which may be the first documented example of the use of “naming rights.” 2

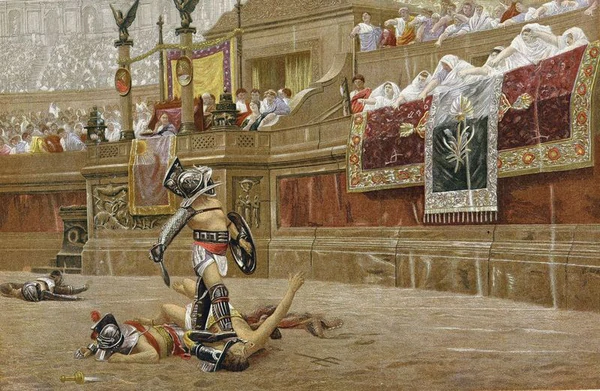

Gladiators and Poetry Sponsorship in Ancient Rome

Not much later, in 264 BC, the first gladiator combat took place. The sport shortly gained in popularity and became a true institution in Ancient Rome. The combats were organized and financed by the wealthy to display their greatness and influence in the community. The combat was advertised on the walls of city buildings, and pamphlets describing the festivities, the name of the organizer (sponsor), the gladiators and their specialties as well as tickets were sold in the streets. The greater the number of gladiators, the larger the show, and the better and more generous sponsors appeared. 3,4 As a matter of fact, Julius Caesar had his own ludus, a gladiatorial training school. He notoriously sponsored a tournament in 46 BC, in honour of his daughter, who died in 54 BC, but he also had political motivations: he wanted to celebrate his recent victories in Gaul and Egypt and thus demonstrate his power.5

Maecenas is another important sponsorship and patronage figure from Ancient Rome. He was a friend and a political advisor to the first Emperor of Rome, Octavian. Maecenas was not only renowned for his diplomatic talents, but also as being one of the most important patrons of young poets, having supported Horace and Virgil, in particular. His name became synonymous with a wealthy, lavish and educated patron of the arts (“mécène” in French).

Patronage Momentum during the Renaissance

The Renaissance was a prolific period for the arts and sciences, which would probably not have been possible without the help of patrons. Wealthy families would open their houses to artists and scientists and help them spread their art or knowledge, not only in Italy but all over Europe. The city of Florence owes a great deal of its cultural, literary and architectural heritage to such families. The Medici family is probably one of the greatest and most famous patrons in history. Cosimo de Medici developed a flourishing bank and initiated the use of patronage and sponsorship as a way to increase and reinforce the family’s, and the bank’s, strength in Italy and in Europe.

Lorenzo the Magnificent continued the family’s tradition, and took under his protection artists such as Botticelli, de Pic de la Mirandole and Marsile Ficin. Michelangelo lived with the Medici family for five years, dining at their table every night in the company of Marsilio Ficino, one of the greatest humanist philosophers of the period. Lorenzo would organize sumptuous festivities and sporting events when distinguished visitors would come. He would also send some of his protégés to influential people in Italy, and that way diffuse his own diplomatic influence. According to Lorenzo’s estimations, the Medici family had spent some 663,000 florins (about US$460 million today) between 1434 and 1471.6

Patronage helped him maintain the image of a generous and caring master in a prospering city. Although his banking, management and political abilities are debatable, Lorenzo surely succeeded in maintaining his family’s influence in a context of great rivalry between wealthy Italian families, thanks to his strategic use of patronage.7

The Medici descendants also did their part and were committed to scientific advancement. Ferdinand 1st supported the promising Galileo Galilei, who, in return, initially named his discovery, Jupiter’s satellites, after his patrons (“Cosmica Sidera” and later “Medicea Sidera”). We also owe them the first natural science academy in Europe: l’Accademia del Cimento (the Academy of Experience), in tribute to Galilean observation and experimentation methods.8

Sponsorship, in its various forms, is at least a 2,500-year-old tool that has been evolving with the times. Before it was more developed and widely used by companies, it was used by wealthy citizens and families to contribute to their society’s well-being, to demonstrate their implication in the community and to extend their influence, as illustrated by Leonidas, Julius Caesar and the Medici family. In the second installment of this article, we will examine how companies took the place of these wealthy individuals and families as far as sponsorship and patronage is concerned, and how sponsorship became the tool that we know and use now.

Read The History of Sponsorship – Part 2

Sources

1 Sanghak, Lee (2009). “The Commencement of Modern Sport Sponsorship in 1850s-1950s”, paper given at Sports Marketing Association Conference 2009.

2 Kissoudi, P. (2005). Closing the Circle: Sponsorship and the Greek Olympic Games from Ancient Times to the Present Day [1]. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 22(4), 618-638.

3 Kathleen Coleman (2011). “Gladiators: Heroes of the Roman Amphitheatre”, BBC. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/gladiators_01.shtml

4 Jacobelli L. (2003). Gladiators at Pompeii, Getty Publications. Retrieved from https://books.google.ca/books?id=NSC0SHEjMe4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=inauthor:%22Luciana+Jacobelli%22&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi1xteozbvUAhWE0YMKHfrNAHoQ6AEIMDAB#v=onepage&q&f=false

5 Keith Hopkins (1983). “Murderous games: Gladiatorial Contests in Ancient Rome”, History Today, vol. 33, no 6. Retrieved from http://www.historytoday.com/keith-hopkins/murderous-games-gladiatorial-contests-ancient-rome

6 The Italian Tribune (2014). “The Medici Family – The Leaders of Florence”, The Italian Tribune. Retrieved from http://www.italiantribune.com/the-medici-family-the-leaders-of-florence-4/

7 Volker Saux (2016). « Laurent le Magnifique, au cœur de l’âge d’or florentin », GEO. Retrieved from de http://www.geo.fr/photos/reportages-geo/italie-renaissance-florence-et-les-medicis-laurent-le-magnifique-habile-prince-des-arts-159441

8 Camille Vignolle (2011). « Les Médicis, Princes des Arts et des Sciences », Herodote. Retrieved from https://www.herodote.net/Les_Medicis-synthese-576.php